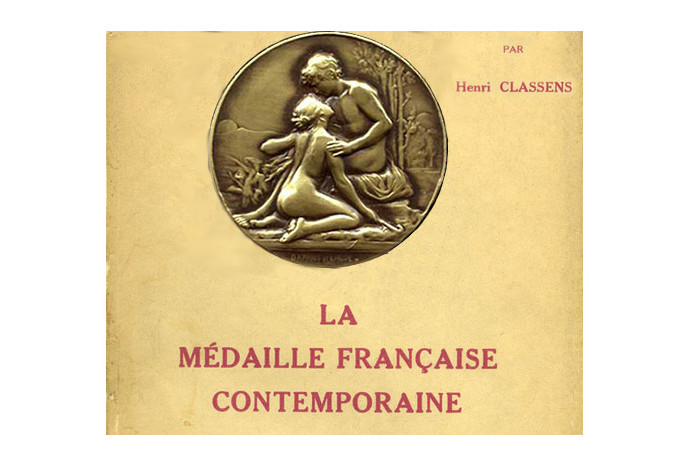

Artists and works by Henri Classens (1930)

French contemporary medal makers can be divided into five groups, according to their inclinations. These groups do not constitute an absolute truth, indeed, some artists belong to several groups; but aside from being greatly justified, they enable us to get a clearer picture of contemporary medal making in France.

Before drawing this picture, it seems necessary to talk of two masters, today both passed away: Hubert Ponscarme and Oscar Roty his pupil. They both took medal making in different directions, but nevertheless had their similarities in several ways. They weren’t the two best medal makers of their time, but their influence has prevailed more than any other artists. It is this double influence, still strongly felt today, the new generation of medal makers is trying to defy.

Hubert Ponscarme, born in 1827, died in 1903, got second prize in the Roman medal contest and taught at the school of “Beaux-Arts”. While medal makers kept within the boundaries of a set of rigid rules, he stood as a kind of liberator. It has already been said that he addressed caption letters as decorative elements, whereas his peers still conferred to them the sharp aspect of letter print.

What must be said above all is that, drawing inspiration from Italian Renaissance medal makers, he blended the patterns with the backgrounds, while the other artists gave their work, in Alexandre Charpentier’s own words – also one of pupils -, “The aspect of a low relief sawed off and stuck on a background”.

In Ponscarme’s works, one can observe a logical and smooth evolution, in which Naudet’s portrait (1867) foreshadows the decided tendency to come, and which will eventually lead to the double portrait of Ovile Yencesse and Marie Chapuis dating from the last years of his life. He simplified the masses, and purposely neglected detail. By lowering the relief and delicately connecting them to the background, he obtained in his later works, soft hues and an overall “painting-like” effect. He devoted himself almost entirely to the portrait genre. He was both a technician and a psychologist. He knew how to scrutinize the model’s conscience and produced, if one may say, as many moral portraits as physical ones.

Oscar Roty, born 1846, died 1911, won the Roman Grand prize. It was he who spread the taste for tablets. He introduced the landscape in the art of medal making, which mostly belonged to painting. In this way, his action can be associated with Ponscarme’s. But unlike his master, he appreciated details and thoroughness, and did not hesitate to “furnish” the backgrounds. He conveyed naturalness to his allegories. He often represented characters of every day life, but his realism is rather superficial. It is this kind of realism which gave birth to genre scenes and anecdote. The official school is represented by artists who take their inspiration from traditionally well established rules. These artists used allegories to symbolise countries, cities, tasks, virtues, etc., through human figures, either naked or draped in the antic fashion, or yet again draped in a totally fanciful fashion. The gestures of these figures or more likely taken from convention that the observation of nature. Horns of plenty, palms, crowns, coat of arms, are regular motifs in their works. In a way, they are the true medal makers, in the sense that their works are well composed, but the elements used being most of the time out of proportion, they do not always manage to create a homogeneous whole. They readily use letters. Generally, the ambassadors of the official school are better at making portraits, than medals where imagination plays a bigger part.

Auguste Patey, winner of the 1881 Roman Grand prize, member of the Institute, professor at the school of “Beaux-Arts”, as an artist belongs as much to the 19th century than the 20th century, we owe him many interesting portraits, such as A. Decrais, French ambassador in Rome (1883), Pasteur (1889), and most of all, the portraits of Marie and Jacques Patey (1894), united on the same tablet. In his compositions he remains conventional; most of the time these display ill-assorted elements, as can be observed on the “Caisse d’Epargne et de Prévoyance du Rhône” medal, and the 125th Anniversary of the “Fondation de Marseille” (1900). With A. Patey, the official school tends to take on the name of “academic”.

Louis Bottée, winner of the Roman Grand prize in 1878, felt comfortable with merely repeating well known subjects. Works like To Poets Without Glory, and The 100th Anniversary Of The Museum (1890), where allegory prevails, are well executed and are not totally without charm. Louis Bottée, in his work, is more of a 19th century than a 20th century artist.

Léon Deschamps, died 1929, addressed conventional compositions with taste and delicacy. He was an honest and skilful artist. His works are elegant and do not display the least sign of strain or effort. His portrait of Gutenberg is not a commonplace interpretation, and it shows softness in the contours. On the reverse side, he put together an ensemble, well composed, and which fits perfectly into the shape of a circle, despite the numerous straight lines and angles. Ponscarme’s influence is detectable in his portraits of Q. Fallières, R. Poncaré, O. Lampué, which are all perfectly executed. One can also mention the small face of Denise Breton as a particularly delightful piece.

Hippolyte Lefebvre, Grand Prize winner in Rome for sculpture in 1892, member of the Institute, truly lacks imagination in his compositions, and his expertise can sometimes be left wanting. He personified the city of Paris as a draped woman, seated while holding a torch and flag. She is carried by a group of draped women, personifying Arts, Labour, and seems to be floating in mid-air…On the reverse, the cityscape of Paris can be seen between blazons, banners, palms, the cross of the “Légion d’Honneur”, and the city’s coat of arms. Other works like: Arras, Patria, France to her defenders (1914), America joining the allies in war (1917), are in the same style. Nevertheless, one may mention his portrait of Mgr Duchesne.

In his medal called Sports, Marie-Alexandre-Lucien Coudray, Roman Grand prize winner in 1893, places two academic figures in the middle of a landscape. However, in his Agriculture tablet, he displays two rather realistic characters: a ploughman and a reaper, busy at their chores. This tablet, freed at last from allegory, becomes a genre scene. His Orpheus, with it’s variations in relief and layout is a very interesting piece.

François Sicard, Roman grand prize winner in sculpture in 1891, member of the Institute, sculpture teacher at the school of “Beaux-Arts”, is related to the official school, much more thanks to his titles than his actual work. He seldom uses letters, and has little concern for composition. His piece called “Tennis”, left at the unfinished stage of a sketch, is remarkable in the truthfulness of the character. In his portraits, F. Sicard proves himself a worthy artist. The portraits of Anatole France in low relief, of the naturalist Fabre, in higher relief, of the deputy Thomson, highly embossed, all bear personal characteristics which express strong personalities.

Charles Pillet, Roman grand prize winner in 1890, has executed several pleasant landscapes. In his pieces Horticulture, Bee Keeping, he seems to have managed to freeze the figures in mid action. He remains most of the time quite academic as in Renowned, and The London Franco-British Exhibition (1908). His Gallia is one of his best works.

Of the sculptor Auguste Maillard, we know a few medals and tablets, of which the highly lifelike portraits of the Coquelin brothers (1911), and the more recent portrait of Galliéni.

For René Grégoire, Roman grand prize winner in 1899, a medal must have meaning, and his works depict topics as; Love, Spring, The Healing of Time, etc. He therefore makes much use of allegory. He furnishes his backgrounds and emphasizes the action and concept by using the setting… Exquisitely shaped, his work bears a highly sculptural aspect. They are of pleasant composition, often without any lettering; if he does make use of letters, they only play a secondary part in the whole. With his particular taste for smooth lines, his love of well-observed and well-rendered human shapes, his respect for proportion and scale, Grégoire managed to earn himself an influent position in the official school. He also sculpts in his spare time.

Alexandre Morlon, also a sculptor, is the author of very remarkable works. Let’s mention for instance among his best medals: “Aux Armes”, displaying the striking profile of a woman warrior. On his Marriage tablet, two draped antic figures form graceful serpentine lines on a foliage background.

Pierre Dautel got the Roman first prize for medals in 1902. He renewed the allegories which were dear to the traditionalists, if not in the subjects, in the producing. He knows how to combine elements becomingly and arrange balanced compositions. The 100th Anniversary Of Carpeaux, the “Syndicat d’initative de Nantes”, and the Drilling of the Haussmann Boulevard medals bear witness. Pierre Dautel, through these works, proves himself to be a medal maker in the true meaning of the word. His Elegy dating from his stay in Rome, almost a sketch, is a pure expression of melancholy. His portrait of Landowski is worth being mentioned. The relief is regular. The outline stands out sharply, whereas the torso is only suggested by a few lines and blends into the background. In seeking to combine graphic pattern with the relief, Dautel took inspiration from Ponscarme; but raising the portrait by a sharp levee, thus cutting out the face’s contours from the background, he was ahead of Mascaux by 20 years (however accidentally).

Of the sculptor Paul-M. Landowski, Roman grand prize winner in sculpture in 1900, member of the Institute, we know the very interesting portrait of the architect Pontremoli, which is actually more a low relief than a medal.

Paul-Marcel Dammann got the Roman grand prize in 1908. He’s a highly talented artist. The influence of his master Chaplain, which was noticeable in his early works, can still be discerned in his portraits. They all bear a family likeness which is one of dignity. In his compositions, he always represents the human body for which he nourishes a kind of passionate cult. He studies the human anatomy with live models, and then interprets it according to his fancy, following the example of the Greeks which he considers as the greatest artists of all times. He favours elegant gestures, quiet and simple draping. In his later works, he emphasizes the line. He likes to keep his compositions condensed, and does away with the unnecessary details. He generally arranges his relief on a circular background, and therefore favours the medal over the tablet. Let us mention among all his works the following; the portraits of Croiset, Roussel, de Castelnau; Nil Sine Minerva, Recollection, Offering, Friend, The Toulouse House of Trade.

Raoul Bénard, Roman grand prize winner in 1911, has not yet showed much personality. So far, he has stuck to academic conventions.

Lucien Bazor, Roman grand prise winner in 1923, is the creator of the new gold coin. He conveyed much more originality in this piece than he has to any other of his works. Despite his decorative research inspired by Turin, he remains a prisoner of academic convention.

In Geese Keeper, Shepherd, And Girl with Rabbits, Georges Guiraud, one of the most recent Rome winners, cuts out relief in a highly decorative manner. He shows more medal making qualities in his Coppersmith. Guiraud is a young man still searching for his artistic identity.

The official school still holds many remarkable artists, such as: René Rozer, Henri Allouard, Roger-Vloche, who are also sculptors, Jean Delpech, Henri Dubois, Léonce Alloy, Jean Vernon and a few others. Landscapers and genre scene artists are still pursuing Roty’s example in some of his works. To symbolise an action, they represent the actual action. If they address the theme of pottery, they show us potters working the clay. The allegory disappears to give way to labourers, peasants, etc… from this to depicting minor scenes with no apparent symbolic meaning, there is only a small step to be made, which leads to genre scenes. Authors of genre scenes are not always great analysts. Their landscapes are rather more fictitious than those actually observed in nature; their common people are most of the time only superficially “common”; yet their small pictures, for want of other qualities, create a diversion; the traditional clothes worn by our country folk, the peasants’ attitudes, the characters and objects taken from every day life, make up an amusing and picturesque range of themes. The public favours the works of these artists, for they represent subjects which are well suited for conversation. As for research in composition, it can hardly to be found.

One of the oldest and most impressive of these artists is Henry Knock. Literate, critic, sculptor and medal maker, he was highly regarded at the beginning of the century. His “Crainquebille”, Sporting Chips, Mother and Child, Nude Woman with Mules, his reverse side of Doctor Garel’s portrait are truly spiritual works. He knows how to create symbols, no less spiritual. We could mention for example the reverse side of one of his portraits of Anatole France. A clever mind, even witty, characterises Nocq’s talent. We owe him many other excellent portraits such as: Gustave Geffroy, Henri Bataille, Paul Margueritte, Maurice Barrès, Anatole France, Gouraud, etc. Nocq was one of the first to apply the technique of medal making to the art of jewellery, a few years before 1900.

Georges-Henri Prud'homme has taken interest in academic themes as much as in modern ones. In City Of Paris (1900), Colonial Union and Ceramic, he repeats the old academic patterns. Whereas his Spinster, Saying Grace, and other more recent works like: Alsacia, Lorraine, are freed from this ruling.

Pierre Lenoir, sculptor and medal maker, author of the Memorial Monument To The Students of the Music Conservatory Killed During The War, has often given into academic formula. But works such as Little Girl With Necklace, The Potters, The Butter, Potato, do not hold the same formality and are quite charming.

Lamourdedieu has represented, in certain works, very conventional figures. In others like The Needle, he took inspiration from day to day life. One of his last pieces Sea Rescue, is aimed to creating dramatic effect.

J. Prosper Legastelois has addressed religious, antic, and modern subjects. His Young Girl’s Profile, dating from 1902, is in many ways considered his masterpiece. Never again has he managed to recapture the same delicacy of touch and expression. Félix Rasumny Also addressed the same kind of themes. One may mention his lying Christ and his studies of Bretons among his best pieces.

René Baudichon favours landscapes; He is the author of Marriage Medal, Silver Wedding Anniversary, Peach and many others works. Baudichon sets in landscapes either draped antic figures or modern characters. We also owe to him several studies of Bretons and Indians executed in quite an unrestrained manner. His tablet Friendship is a charming image picturing the fashion trends at the beginning of the century.

Madame Mérignac is mostly renowned for the medals and tablets she devoted to fencing and to the French Provinces. In the later, she symbolises the provinces by woman portrayed from the waist up, emphasizing more on the picturesque qualities of their headdress, than on the ethnical features of the girls from Normandy, Bresse or Charente. Madame Mérignac executed a few of her works in clay, enamelled in various colours.

In his compositions, Fraisse is often academic. He is best as a Sports medal maker, as he says himself. Having practised nearly all imaginable sports, he takes inspiration from these activities for his work. Nobody knows as well as he does how an athlete breathes, which curve best suggests an arm about to throw a ball.

We must here make room for André Schwab. He is the author of a large range of works, all impeccably executed. His reproduction medals like, Singing, Saint Ann, or his interpretation works like Leonardo da Vinci, Michel-Angelo, are excellent pieces of this particular genre. But it is in pieces inspired by Brittany that he excels. In these, he shows deep insight and proves himself perfectly well-informed of the Breton “type”. Mamm Gooz Pennec, Jean-Marie Kervella, Mamm Gooz Kervella, are all true, lively, characteristic figures. What can be said about the reverse side of La Bigoudène, except that it is particularly representative of medal symbolism. In scenes like: The Rosary, he demonstrates qualities as a sculptor by emphasizing the volumes. One of his great qualities is that he knows how to bring a piece to its completion without loosing any of its spontaneity in the process.

Louis Muller, second place in the Roman contest of 1929, has a true feeling for life. He’s a curious mind, struck by the amusing way the trumpeter blows into his instrument, the simple gestures of the knife grinder or vegetable seller. These attitudes interest Muller, the attitudes in themselves, therefore he doesn’t necessarily feel the need to place his characters in a setting. With his Resting Horse, he is keen to show as much truthfulness as possible. This honesty and sincerity of vision can also be found in his portrait studies, a subject so broadly addressed and of such original layout. These portrait studies or more “medal-like” than any of his other works. Louis Muller proves himself to be a dominant figure among young medal makers today.

By some of their works, the following artists can be affiliated to the group of landscapers and genre scene authors: Louis Patriarche, Firmin-Pierre Lasserre, Louis Desvignes, Marcel Burger, Berthe Noufflard more commonly known as a painter.

Ponscarme’s school is only represented by a handful of artists, yet very worthy ones indeed. Their names are : Ovide Yencesse, Abel La Fleur , Paul Niclausse et Albert Herbemont. None of these artists have ever won a Roman prize. Having brought Ponscarme’s precepts to their highest level, they owe to him a rather larger rendering of relief, a peculiar taste for nuances and delicate hues. But unlike Ponscarme, they have drawn their inspiration from every day life; nevertheless, their master’s concern for rigorous observation in portrait can also be found in their character studies. Their works cannot only be considered as anecdotes; they show qualities in the choice of the subjects, in their truthfulness, and also in the particular technical methods in which they were produced.

Ovide Yencesse is today the director of the Dijon school of “Beaux-Arts”. In his most typical works, the relief is hardly noticeable, and the lines indicating in part or in whole the figure’s contours are partly faded. The relief is blended to the background of the medal or tablet, and seems to rise out from a light fog. These pieces have earned him the name of “The Carrière of medals”. This very pictorial conception of the medal allowed him to express with a rare delight the softness of a child’s kiss, of motherly love, the immateriality of Christ crucified. In his earlier works such as; Pierrette the Poor, Virginie the wise, and others, he placed his characters in an appropriate setting. In truth, Yencesse was more interested in creating “paintings” than in making compositions. He sometimes took inspiration from Greek antiquity. He treated his portraits like any other work, in blurred relief. Despite his more recent medals of higher relief and sharper design, Yencesse remains the master of chiaroscuro in medal making.

Abel La Fleur has always given great attention to silhouette; his relief, even the most subtle, has neatly drawn contours. He sometimes managed to create a softness of relief, which gives a truly exquisite effect under the play of light. We owe to him pictures of women from the beginning of the century which, instead of aging with time, take on a particular style; and bathers harmoniously and curvedly shaped. On the reverse side of The Bath, he displays a landscape, stylised in a way which is unique in the history of medal art. His portraits are of higher relief than his other works. Generally speaking, his later medals, compared to the older one, also have higher relief. La Fleur doesn’t often make use of letters, and his works are more like “paintings” than true compositions.

Of this four artists group, Paul Niclausse is the one who has the most of the sculptor attributes, probably because he also works on free standing sculpture. The medals of Cardinal Luçon, The Union Insurance Company, The Digging Of the Suez Canal, are already highly interesting in their exquisite relief. In his last two works, Niclausse made use of allegory, but the gods Minerva and Mercury have human anatomies; they cannot be said to be academic in any way. The reverse side of the Cardinal Luçon, deserves a particular comment. Niclausse did not seek to reproduce every detail of the Reims cathedral, he observed the masses and outlines, and was able to keep the truly monumental aspect of the building. From this point of view, it is a nearly unique piece in French contemporary medal making; Niclausse is now a professor at the “Ecole Nationale des Arts Décoratifs”.

Albert Herbemont really more of a medal maker than the others, indeed, he has strong concern for composition. His Poultry Farmer is an excellent proof of this. He willingly makes use of letters, and often includes the caption into the overall composition. He concaves his portrait, as his other works, in large relief with neatly drawn contours. The medal of Mgr de Carsalade du Pont is a typical medal which could be called a master piece. The crosier, mitre, coat of arms, letters, the very posture of the figures, make up a perfectly balanced whole. The reverse keeps a symbolic aspect and does not represent a landscape. Sometimes, like his Saint Christopher and other works, Herbemont shows a certain awkwardness in the rendering, which is not always found wanting in charm.

On the opposite side of Genre scene authors and Ponscarme’s school, is the school o builders and decorators. For these artists, the medal is, and must remain, sculpture, which means that it mustn’t borrow any features from painting, neither hues nor perspective. Therefore, they favour bare and flat backgrounds, and they neatly draw the contours of their relief. They reject the “painting”, the anecdote, the subject being sufficient in itself. The subject is only of secondary importance for them; for them it’s only a pretext to set up layouts, arrange volumes, curves and lines. If they take inspiration from antiquity, it is not to slavishly copy the pieces, but rather to reinterpret with a more modern vision. The builder and decorator group includes most of the medal makers belonging to the new generation. An interesting fact, is that these artists come from very various cultural and educational backgrounds.

It would seem proper to mention first and foremost: Léon-Claude Mascaux. L.-C didn’t really start producing until after the war, after having been trained as a free auditor at the Julian Académie. He ceaselessly uses the process of hollow carving in plaster, and only makes medals, never tablets. In fact, to him the art of medal making consist in “adorning, decorating a disc”. He does not claim to try and reproduce nature accurately. When he does take the human figure as a subject for, it is only a pretext for curved lines, which he treats in the manner of large scale sculpture, the background playing the part of a wall. At the 1921 “Salon de la Nationale”, he did not hesitate to introduce his works as “research on style and plastic”. He was the first to react to Ponscarme’s hazy and blended manner in a truly thought over and consistent way, by sharply cutting out the relief from the background. In his portraits, he shows the same desire for stylisation. For his sports medals, he has found simple and meaningful symbols; a nice change from what we are used to seeing. More recently, he addressed quite successfully the genre of satire, genre which has always repelled medal makers because of its difficulty. Lascaux has only truly influenced a handful of artists, but he stimulates reflexion among almost all of his peers. Therefore, he holds an important position in today’s French medal making influences.

Henri Bouchard got first prize in Rome for sculpture in 1901. He is the author of historical medals, where are combined a perfect knowledge of documents, a sure hand, and a high concern for composition, let us quote: Les Bourguignons Salés, The Chronicler Alain Bouchard. Modern life inspired him some charming works treated with much decorative attention as in There once was a Shepherd girl, The Grape Harvest, etc. On another level, his memorial medal of the “Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs” (1925), was executed following an academic program. “The Decorative Artists Bring to the Exhibition the Product of their Creation”, is a truly modern piece. Bouchard seems to excel in portrait making; “A play of shapes and not of details”. His portrait of Frantz Jourdain, in its sobriety ,the strength of its relief, the layout, the arranging of the letters, the intense feeling of life it expresses, could be considered as the master piece of French contemporary medal making in its genre.

Henry Drospy, second prize in Rome in 1908, is the most productive of medal makers.

For many years, he indulged himself in anecdotic scenes. These were: Breton Begger (1908), executed in a very free hand, Milk Maid (1913) displaying very “ponscarme-like” hues, Procession (1922), Tenderness (1923), etc. But in Child With Bathtub (1936), he takes on a new path. Then came, The Seasons, The Elements, etc., which bear a purely plastic quality. These works are made in rather rough and powerful relief, and their motifs are interpreted in modern fashion, tending towards simplification. This synthetic conception can sometimes be rather bold. He goes as far as symbolising electricity by the two nude bodies of a man and woman! Amongst the portraits executed by Drospy, let us mention particularly Victor and Thérèse Canale, of ingenious conception, and the truly remarkable Nicolas Roerich.

Maurice Delannoy has not been to any school, he taught himself medal making. On a given surface, most of the time a circle, he balances his compositions, almost always using the human figure. His anatomies, more or less stylised, are first studied from a live model. Some of his nude figures, as in Woman with Parrot, are discreetly tinted with sensuality. One can observe in Dolls, Woman With Grapes, The Advice Of Love, a very modern spirit and touch. His self portrait has a very lively expression. Let us also mention the delicate profile of Sarah which is in its symbolism, a true medal. Delannoy very seldom uses captions.

The sculptor Pierre Poisson, author of the memorial monument to the deceased in Le Havre, also makes medals. He devotes to the later a particular attention to line, balance and proportions. For Poisson, “The medal is a small scale monument and its main quality is its architecture”. Medals like The Parisian Hall Of Trade, the “Exposition Nationale des Arts Décoratifs” (1925), the City of Le Havre, as well as Sainte Theresa, are excellent illustrations of these principles. On the Parisian Hall of Trade medal, Poisson allowed great importance to letters, and did not hesitate to arrange his figures symmetrically.

Raymond Delamarre got first prize in Rome for Sculpture in 1919. We owe him the colossal and utterly modern figures standing on the Defence Monument of the Suez Canal. In his medals, he favours line and composition, as testifies the reverse side of the memorial medal of the 60th anniversary of the Canadian Confederation foundation (the head side is not of his making). His portrait of the geographer Jean Brunhes, is a psychological portrait. The reverse side is a logical choice indeed, yet manages to hold the appeal of novelty.

André Lavrillier, Roman grand prize winner in 1919, is a builder; His works are impressive by their architectural quality. With his Leda, executed in Rome, he his placed on the front row of medal makers. Then came other works which did not refute the great hopes which had been put in him; like the portrait of Georges Renard with its vigorous relief. The reverse side of this portrait is of utterly modern making. For the medals of the Hartmannsweilerkopf Monument, the Monument To The deceased of Nice, Mickiewicz Monument, Lavrillier drew from the monuments themselves his expressive themes. One cannot, under such conditions, separate the names of the authors of these monuments from the names of the medal makers, nor forget to mention the merit owed to both party. Anyway, these three medals bear strong qualities; the Mickiewicz Monument, the most interesting of all, would be worth a study in itself. But let us be satisfied in admiring, on both sides, the unity of style; the grandeur of the contours, creating such powerful hues; the placement of the symbolic figure, unsymmetrical yet perfectly balanced on the medal’s background.

An evolution can be observed in the works of Pierre Turin, grand prize winner in Rome in 1920. His first works reflects the academic style. However, in his later more characteristic works, he shows a delicate and elegant taste for curves. The relief is delightful; the stylising is always supported by a accurate regard for shape. Often he indulges himself in detail. His medal: Nil Sine Minerva, conceived in the Greek style, and Saint Francis Of Assisi, so different from the religious medals we are used to seeing, proves than he is able to express himself in various ways. From the hexagonal shape which held his interest for years, he switched to the circle. Turin is the author of the new silver coin. He is one of the rare medal makers who know how to engrave steel. One may also mention that he also paints in his spare time.

Ernest Blin changed his « manner ». In his later works he’s been seeking stylisation. The relief seems carved out in great strokes, as in the medal he executed for the International Aeraunotics Federation, or in Goat Head. In this manner, the low relief of the medal takes on the aspect of a full scale sculpture.

Jean-Auguste Briquemont followed night-classes at the Paris City Hall in drawing and sculpture. In truth, he managed to become one of the most personal of medal makers, owing only to his own tenacious efforts. He has the utmost sense for symbolism. Sometimes, he carves relief in large levelled layers, like in his piece called Dome, occasionally he even simplifies to the extreme and restricts himself to simple contours, as shown in Maternity, Woman with Crib, Mother and Child. In his last works, he is more of a drawer than a sculptor. Generally speaking, he disregards detail; he comes up with original and unexpected layouts; he also shows clarity and eloquence in his expression. He has never yet made use of letters.

The Jeweller A. Rivaus is also a medal maker. Supporter of the direct carving method, he executes his medals according to this process. Among his works, Victory is worth remembering.

Marcel Renard practises sculpture as well as medal making. He has sometimes treated his medal in low relief, and at other times in very sharp relief. He started by drawing inspiration from nature, as for example in Goat, before turning to stylisation. His Woman Pianist marks an intermediate stage. With the strongly architectural piece The Flute Player, he asserted himself as a highly singular artist.

Simone Boutarel readily borrows her subjects from wild life, and successfully seeks a decorative effect. She is highly praised for having drawn inspiration from the circus. Here at hand is a whole universe, totally untapped by medal makers, which is highly suitable to decorative compositions, as she rightly proves in her Woman Rider.

The sculptor Roger de Villiers made tablets in an architectural style. His Jane of Arc as a shepherd is a piece both well executed and singular. The heroin, the sheep, the landscape in which the scene takes place, are treated in a stylised manner in large surface cut out and arranged one next to the other. Emilie Monier with Bacchante or Fauna; Eugene Doumenc with Child With Pigeon and Woman With Goat, are both related to the group of decorators and builders.

The independents are a group of artists which are, in essence, defiant of any imposed discipline. They do not work according to standard principles, but let their nature express itself naturally, according to the circumstances. They are independent in the first meaning of the word. Among these medal makers, we will mention three of the most significant names. Albert Pommier, Henri Navarre et Léon Drivier.

The Sculptor Albert Pommier, with his small scale low relief, is among the best medal makers of his time. His works can be grouped in several categories: portraits, medals relating to war, medals relating to Algeria, nude studies. His “poilus” (First World War soldiers) in large and blurry contours, stand out from the little soldiers, or should we say little men, represented far too often on the medals executed during and on the subject of the war. The Bread Chore, for example, is a truthful picture of the modern warrior, as if taken on the spot. The Arabic Musicians and The Arabic Dancer are less straightforward, but just as truthful, however they do not bear the same blurry aspect. In the Oued, Pommier was more concerned with composition, and therefore gave us one of the most beautiful medals of our time. What Pommier appreciates, is the sense of life without artifice, observed directly from nature. And indeed, a great deal of life springs from his portraits, nude women, and from all his works as a matter of fact.

Henri de Navarre is renowned as a glass artist, sculptor and medal maker. His medals, whether it be in their subjects, conception and execution, are truly liberated art works. They are also singularly expressive, yet remaining most of the time in the form of sketches, sometimes drawn with great strokes of the chisel, at other times made up of a of a few pellets, as in the medal called Blind. Of his medals and tablets, the most tasteful are the ones inspired from Russian ballet and which he called: Scheherazade. Dancers of vigorous contours and supple, skittish silhouettes, with such truthful gestures, so very typical…

But these works, however great, could not yet make us forget the wittiness of his Juliette, the sourness of his love, the unexpectedness of his Marriage tablet.

The medals of the sculptor Léon Drivier are of a different conception all together; they are not marked by the usual milestones of a continuous evolution. In truth, Drivier leans in this or that direction according to the conditions at hand. Thus, the Paul Deschanel has an official quality, while Love and Amazon take on a Rodin-like air. Certain medals represent characters observed from nature, others take on a more interpreted shape. The Descent from the Cross, in its general composition and expression of pathos can be related to the art of the Flemish primitives. All these medals have in common a very vigorous manner of sculpting. Drivier does not show any particular attention to the contours of the medals. He engraves his medals in hollow, from different materials, and is probably the only one who always executes them directly in their definitive scale.

In addition to that, we owe many great works to a few more artists, various talents, which cannot be classified in any of the groups mentioned above. They are: Elisa Beetz-Charpentier, Anie Mouroux, Geneviève Granger, Georgette Daveline, Aleth Guzman, Roman grand prize winner in 1929, Ernest Révillon, Joseph Picaud, Paul Roussel, Maurice Thénot, Paul Richer, R. Amandry. Finally, we could mention the painter Charles Dufresne, who started his career in medal making, and the sculptor Antoine Bourdelle (died in 1929), who executed a rare few small scale, low relief medals, like the Czechoslovakian “Croix de Guerre”.

commentaires

Laissez votre commentaire