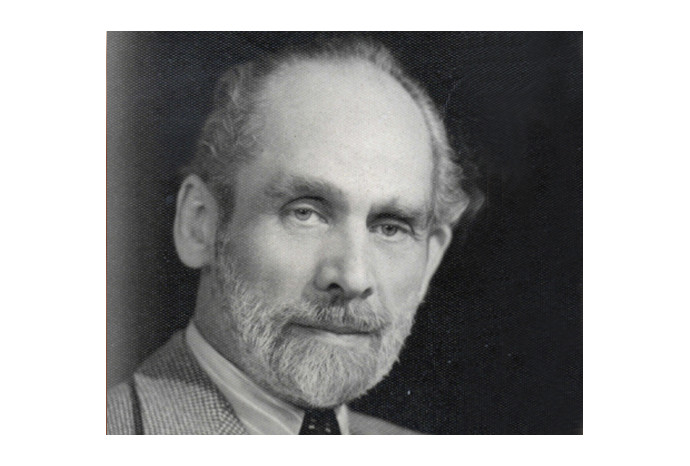

The art and technique of the medal by Henri DROPSY

By M. Henri DROSPY MEMBER OF THE INSTITUTE

In the art of pressed medals, we can consider two different processes:a medal from the 17th century, for example brings the burin to mind by the precision of its chiselling, whereas a fifty year old medal, by the suppleness of the model, rather evoques the sculptor’s firmer chisel. These two different tools define two different techniques.

To pass from the old one to the new one, a machine, inspired by the pantograph, had to be invented and progressively adjusted. The perfecting of the device took more than a century.

In 1729, La Condamine presented to the Science Academy a machine which could execute all kinds of regular and irregular contours, and another to carve various types of rosettes (1). In 1749, in the book “L’Art du Tourneur” (the Art of Milling), P. Plumier already mentions this invention “for the purpose of reducing profiles” but does not yet seem to be acquainted with the “tour à portrait” (portrait mill). In the midst of revolutionary torment, Bergeron in his “ Manuel du Tourneur” (milling handbook), and after quoting Plumier’s passage, declares that both machines submitted to the Science Academy by La Condamine “ had presumably led to the invention of the tour à portrait”.

The first few attempts, having for a long time remained quite unsatisfactory, weren’t found any practical use. But after several modifications were brought to the first version, Bulot the Younger completely changed the construction of the machine, simplifying it in order to obtain more accurate and reliable results.

If we are not mistaken, Bulot’s machine has lived on until our day and age; but at the “Musée du Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers” (Conservatory Museum of Arts and Trades), can be found a “tour à réduire et à graver” (reducing and engraving mill) by Ambroise Wohlgemuth, dated from 1820, which already bears the main characteristics of the ones we use today: two trays situated on a same level pulling both the model and the reduction along in a circular motion.

Later on, on the 22nd of March 1837, Achille Colas registered a patent “for devices used for the copying and mechanical reproducing of any kind of sculpture and in any kind of material”. He first built in 1847 a tour à réduire for medals, similar to Bulot’s, to which he had brought a few improvements.

(1) Knurls and spurs

Around 1880, the knife used to engrave steel, which could not execute the work in one go, was replaced by a mill which thanks to its circular motion could guarantee the most accurate and rapid execution.

The machine à réduire (reducing machine) was thereby complete, and its use has been expanding ever since.

Let us now examine the influence of the tour à réduire on the evolution of the medal at the end of the 19th century.

This new possibility medal makers were offered to execute their work in various materials, and in larger scale, instead of directly engraving on steel in the definite size, made it easier for them to obtain a less restrained overall effect, and enabled sculptors to also produce pressed medals, which would have been impossible without a mill.

Some even used models which were no more than sketches. These advantages, however, do come along with a few inconveniences, for engraving directly on metal has the advantage of being more precise and of sharper execution. Take for instance, not only the admirable medals of the XVIIth century, but also the highly decorative coins of the middle ages, executed in such a charming style by hollow engraving on metal.

Alongside the art of engraving pressed medals, was invented five hundred years ago by the brilliant Pisanello, a new mean of expression: the cast medal. “Since de Syracusians, according to Elie Raufe, we have never come across such steadiness, such delightful and subtle patterns, such penetrating and vigorous elegance of expression”

Yet, this medal is slightly different from the coins engraved at Syracuse. It is obtained by casting in wax or plaster, which gives it a whole new aspect.

The tour à réduire enabled the merging of two techniques which had remained totally separate up to then: casting and engraving; it automatically executes the bradawls and corner which the craftsman used to have to work with the chisel.

The medal produced in this manner doesn’t have the character of an engraved medal, but nevertheless keeps the aspect of the original, i.e. the model.

Thanks to this device the sculptor/medal maker Alexandre Charpentier, who sometimes represented nude women with brutal truthfulness, produced from 1885 to 1900 portrait-tablets which are still considered amongst the best of his period.

He would make average scale models, about twice as big as the final version. Following the reduction, the work fortunately conserved nearly all its original consistency.

What a prime individual Charpentier was! May I recall by the way, what an independent spirit he was? One of the last to embody the “Murger Bohemia”. He even went as far as living on a houseboat for a while. He claimed that the best way to give a medal a nice patina, was to have it undergo many manipulations. Therefore, he kept his pockets filled at all times

But to return to our subject, another example of a piece which couldn’t have existed without the tour à réduire, is the equestrian portrait of Ratier executed in 1884 by Frémiet. “One of the best and most worthy medals of the contemporary school”, according to Henry Nocq.

And Henry Nocq was an expert, being at the same time a medal maker and a goldsmith, as were his 18th century predecessors. He was also a great scholar, a regular visitor if libraries; he wrote many very serious books on bradawls in the goldsmith trade, on Pisanello, on Duvivier, etc; his medals made for pressing were scaled down, the ones made for casting withheld their original size..

Could they have been cast by the famous Antonin Liard, who died in 1940 at the age of 81, whose casts are still famous today?

Probably. Having devoted himself to constant research, this excellent craftsman knew all the secrets on his difficult trade. Only absolutely perfect pieces were allowed out of his workshop. He has been known at times, in his constant quest of perfection, to correct some invisible flaw by hand with an engraving knurl.

Meanwhile, Tasset was executing and improving the works of many an engraver and sculptor. He had tried to expand this reducing process to the confection of plates used in post-stamp printing. Did these stamps have the same sharpness and fullness as the chisel engraved vignettes?

We haven’t had the chance to see these attempts with our own eyes, but direct engraving, is once again in our opinion preferable to anything obtained by mechanical or chemical reproduction.

Must I mention that in France, the arts of engraving aren’t encouraged enough? Coins, stamps, bank notes, which pass on a daily bases in front of the eyes and through the hands of the public, and obtained by engraving, should be used to develop general good taste, and serve as tokens of the French genius abroad.

On second thought, the machine often requires the use of engraving.

Tasset, and his successor Hozanna have mechanically reduced among many others, the works of Chaplain, and it isn’t unreasonable to mention that it would have been wise of the author to make the bradawl touch ups himself, instead of entrusting this task to the reducers, not that they weren’t good engraving craftsmen, but they didn’t always remain loyal to the author’s intentions.

The truth is, touch-ups must always be done by the artist who created the model; hence the need for medal makers, even when employing a machine, to have perfect knowledge of steel engraving techniques.

But against our deepest intentions, let us not mention Ponscarme’s memory lightly. This great artist, even though he created some highly sensitive and remarkable models for the use of the “tour à réduire” only, was capable, when he thought it necessary, to perfect and complete his work with a chisel.

Indeed, his works were as truthful as was his character. Of uncommon straightforwardness, he was unfortunately equally awkward when it came to polishing his reputation or backing up his students in front of an examination jury. Consequently, they had written on the door the workshop he directed: “This road does not lead to Rome.”

If one considers that this joke was the first thing read by new arrivals at the door of the premises, where the attendants were supposed to be preparing themselves for the Roman contest, one may find it quite witty.

We might add that Ponscarme has always kept a cold head, even when impressionism prevailed. This art form, which eventually won him over, did no keep him however from training many medal makers who eventually left their mark on other artistic currents.

Among them, honour to whom honour is due, was Roty whose “sower” coin made him forever famous.

By studying 18th century art, he most likely drew his inspiration from the charming soft-carved illustrations by Moreau, Boucher, Gravelot, Eisen, Marillier, and also from medals by Jean Duvivier who, following in Mauger’s footsteps, was keen on representing picturesque truthfulness, and dared to use real perspective and the attributes of painting.

Roty exercised a paramount influence on his peers of the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century.

Atmosphere is sought after, faraway landscapes disappear into the fog, skies cloud up, figures blend into backgrounds which progressively start filling up with detail. Medals became like small paintings, intermediates between sculpture and painting, and if the relief remains rather thin, that is because the machine wasn’t yet powerful or accurate enough to reduce strong embossment.

The group under the influence of Roty abandoned the steel engraving technique, in opposition to medal makers of the beginning of the 19th century, who were so eager to reach technical supremacy in engraving, they ended up forgetting all about artistic expression. Unquestionably, it has always been necessary for the artist to be the owner of his trade. Nowadays, it is also necessary for him to be the owner of his machine. It is available to him at all times, and can be used soundly or badly depending on his knowledge of the machine’s possibilities. Should there be a difference in scale too great between the model and the reduction, it would result in an exaggerated shrinking of details, which once scaled down are no longer adapted to the measuring of eye and hand. Or else, should the machine be wrongly set; should the pin skimming over the large scale model and the mill engraving the bradawl not be set at the exact same angle and proportions, it would result in the thinning or thickening of the shapes

All in all though, the tour à réduire did open the way to a new age of medal making, yet chisel engraving shall always conserve its prevailing position in the techniques of modern model making.

Our generation which has seen the birth, and now witnesses the expansion, of the new technique brought on by mechanization, has also known in its youth the old traditions of the trade. These two techniques lived side by side for a while, and then as time went on, the new replaced the old almost entirely.

Thus, in my father’s workshop, J-B. Emile DROSPY, we still proceeded for certain tasks as did the engravers of the 15th century.

A highly detailed study was carved concavely. From this study an imprint was taken. We then obtained a steel relief subject. This relief once corrected, carved and set, was pressed into a bloc. The subject took once again the shape of a concave steel surface. The inside was filed to the desired depth, the inscription was executed with the help of letter stamps which were hammered, that is pressed, one next to the other. The hollow motif thus finished and cast made up the corner.

Until 1870, when the pendulums became strong enough to press entire medals, including the letters, we still, even for a small-scale pattern, continued to first press the subject, then polish the background, and finally hammer the letters.

This long and meticulous work demands from the craftsman adroitness, good drawing skills and impeccable eye sight. Most of the time, his eye closely pressed to the magnifying glass, nervously gripping the chisel in his right hand, the engraver needs to summon his full attention, and requires abundant light. That is why, by the way, they tend to nest in the upper-floors of buildings. They seek, preferably, those beautiful 17th century houses of the “Marais” quarter, still numerous in the “rue Beaubourg” and the “boulevard Beaumarchais”. The “bourgeois” had abandoned them, giving way to industrious craftsmen.

Against the window, stands an elaborate workbench, where each craftsman in his own booth, sits in front of a cast iron ball, hardening the steel among a clutter of tools, chisels, shears, bradawls, oiling stones, magnifying glasses. In the evening, a lamp is placed in the middle, surrounded by water filled globes to condense the light.

In J-B Emile Drospy’s workshop, in the back facing the window, gently purred the lathe. Electricity had not yet been installed into the buildings; a painstaking man would spend the whole day, stepping on the pedal, putting gears and belts into motion.

Once the reduction was finished, it had to be pressed in order to obtain the corner which would then be used as the hammering tool. It was in Villemin’s workshop, “rue des Coutures-Saint-Gervais” in the “Marais”, that the engravers went to execute this task. He would forge steel blocs, cast them, fire them, and rent out the powerful pendulums which his clients needed for replicating and pressing.

They found other partners, firstly the reduction maker Janvier on “rue de Montmorency”, who was one of the first to add a drill to the lathe, and Combet on “rue du Temple”, a skilled craftsman who used to carry out delicate tasks, i.e. the thin border which sometimes lines the medal. Inexhaustibly talkative, with his white beard and long dark blouse, he was the kind of conscientious craftsmen who loved his trade, and was always on the lookout of anything he may still ignore.

Would you forgive me for regretting that this concern for meticulous work is so rare today?

The fault may be imputed to the machine which takes on all the effort, it should be reminded today that man can only achieve true fulfilment through what is acquired at this cost. We must by all means, strive to get young people to develop the same taste for perfection. At the “Ecole des Beaux Arts”, where is bred tomorrows generation, we try to teach the young medal makers, as they toil to achieve their ideal conception in each of their productions, to use all the possible resources of their talent and trade.

They must knowledgeable enough to face the constant problems they will have to solve, which vary infinitely. To succeed, one needs to acquire extensive knowledge of the principles which rule medal making. First of all, it is mandatory to consider composition and expression, essential qualities which are necessary to the intelligence of the piece, and to the emotion which it should stir in the observer’s soul. And most of all, our youth mustn’t be mistaken on the difficulties, and nobility specific to the art they practise.

One of our former Perpetual Secretaries, Quatremère de Quincy, brought them to light in this very spot on the 6th of October 1821, by reading this note which he devoted to Benjamin Duvivier:

« The art of composing medals consists in reducing to the finest detail every subject, action, picture, in order to bring to light, not the insignificant part of the whole, but the whole all clearly represented by only a part. The mistake of some modern schools of this kind, was to believe that a medal should look like a miniature painting… As large as a medal’s surface may be, it’s still one of the smallest spaces a composition could occupy; and, paradoxically, it seems it is nearly always the most extensive and plentiful subjects one is asked to reproduce. Thus the obligation of the artist to grasp, in each subject, the pattern or emotion which constitutes it’s central or main point. Consequently, this skilful system of abbreviation brings each composition back to it’s simplest expression, of moral and physical values; but also one has the obligation to attribute to each character and figure, it’s value in this ideal language of which they become the symbols; And these values consist in majesty of shape, grandeur of style, and energy of character”.

It could not have been put into better words, and the medal maker, truly devoted to his trade, who aligns his hand and thoughts with these excellent conceptions, is all the more likely to do well.

commentaires

Laissez votre commentaire